By Po-Hsiang Ou[1]

Abstract

The concept of risk has an economic origin that associates ‘risk’ with opportunities and potential benefits. This ‘economic view’ considers risk as an inherent part of business decisions. However, dominant literature of risk regulation tends to exclude this economic view and focuses mainly on controlling risk as avoiding unwanted future hazards. This paper, by empirically examining inter-expert risk communication in relation to the promulgation of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) fiscal rules, seeks to shed light on the role of economic expertise and the economic view of risk in risk regulation.The fiscal rules laid down in the Maastricht Treaty require Member States to keep their deficits under 3% and debts under 60% of their GDP. These ceilings have defined excessive deficits and conceptualised the ‘risk’ of the EMU. Through archives and interviews, my findings suggest that, for the purpose of risk communication, economic experts have formulated a closed club network, adopted an optimistic culture, and chosen strategically some arbitrary risk regulation standards. In the case of the EMU fiscal rules, economic expertise and the economic view of risk were politicised.

As a former central banker, I cannot help being aware of the risks. But there are also risks, having created such strong expectations if it is not done. And there are opportunities, too, provided we know what we are doing.

– André Szász[2]

I. Introduction

For the former Executive Director of the Dutch Central Bank, ‘risks’ of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) coexist with opportunities. While the dominant practice of ‘risk regulation’ focuses on avoiding unwanted future hazard in issues related to the environment or new technologies, the economic view of risk tends to associate ‘risk management’ with potential benefits. In this paper, I argue that this ‘economic view’ of risk is a special risk conception of economic expertise, which plays a unique role in risk regulation and risk communication, but often neglected by empirical studies.

The negotiation of the EMU fiscal rules (also known as the excessive deficit criteria or the Maastricht criteria) is a good example for analysing economic expertise and the economic view of risk in risk regulatory regimes. Through examining the creation of these rules, I seek to demonstrate empirically how an economic view of risk operates during the discussion of risk regulations standards among experts. In other words, this paper is about how economic experts conceptualise and communicate risks in relation to the process of standard-setting.

Risk communication among experts is an under-developed topic in the field of risk regulation. In fact, ‘inter-expert risk communication’ with an economic view of risk depicts a very different picture that goes contrary to conventional wisdom of scientific policymaking. By looking at the promulgation of the EMU fiscal rules, this paper shows that: (1) economic experts work closely with policymakers as a closed ‘club’; (2) economic expertise tends to frame and discuss risks with an ‘optimistic culture’; and (3) the outcome of such inter-expert risk communication process is ‘arbitrary’. Investigating inter-expert risk communication provides an alternative sociological lens to analyse standard-setting in risk regulation. As my findings suggest, ‘risk’ is more than ‘probability x impact’, because in the case of the fiscal rules, economic expertise and the economic view of risk were politicised.

Section 1 will explain why the economic view of risk matters and why inter-expert risk communication in relation to standard-setting is an important focus. Section 2 will introduce my case study, i.e. the making of the fiscal rules. Sections 3 will discuss the three major findings of this paper: the club structure of risk communication network, the optimistic culture of economic experts, and the arbitrary results of risk regulation standards. Section 4 will conclude with some thoughts for future research.

II. The Economic View of Risk

Economic expertise, in particular the ‘economic view’ towards risks, is of critical importance to the study of risk regulation. However, while research has identified the complex and ambiguous nature of ‘risk regulatory concepts’,[3] the influences of various conceptualisations of risk in regulatory practice remain under-studied. Economic expertise and the economic view of risk require further unpacking. In this introductory section, I will first discuss why the economic view of risk matters; then I will explain why I focus empirically on risk communication and the making of risk regulation standards.

A. WHY ECONOMIC EXPERTISE?

Expertise plays a very crucial role in regulatory practice, especially in areas related to science, technology and risk. ‘Risk’ is often described as a potential future hazard that may impact the general public, but needs to be identified and controlled through governmental interference informed by science.[4] Studies in this field focus on either improving the scientific methods for risk assessment[5] or strengthening the public participation in risk decision-making.[6]

While most studies focus on analysing the tension between science and democracy, some argue that this science/democracy dichotomy is missing the point.[7] I argue, on a rather different note, that, in order to decide whether this science/democracy dichotomy is really the fundamental question of risk regulation or not, the functions of expertise in a risk regulatory regime need further unpacking. It is essential to examine the epistemological basis of the expertise and to analyse its influences on practices of risk regulation. Experts, in this sense, are those who contributed to the adoption of certain epistemologies of risk.[8]

To this end, economic expertise is particularly important. There are three reasons for this. Firstly, in a theoretical sense, the Foucauldian perspective of ‘governmentality’ explains how knowledge can be deployed as the ‘art of government’, with economic expertise as a prime example.[9] The ‘discovery’ of the economy, as a new way of thinking about power, has shaped the emergence of an ‘economic government’ as part of the modern constructs of governing behaviours.[10] Secondly, in terms of regulatory practice, economic tools such as cost-benefit analysis (CBA) are widely used in different areas of regulation, in particular policies related to risks.[11] The economic discourse is actually pervasive in public policy debates. Finally, a utilitarian logic is embedded in economic analyses, and its implication in risk evaluation may be conflicting with other ethical values such as egalitarianism and liberalism.[12] Economic expertise seems to approach risks differently when compared with other ‘hard’ sciences or engineering as purely providing scientific evaluations. Most studies in the field of risk regulation, however, focus on issues related to ‘technological risks’,[13] such as pollution, food contamination, health, nuclear power or other issues associated with new forms of technology. It was only until recently, due to series of economic crises in Europe and worldwide, that ‘risk of economic activities’ started to receive more academic attention.[14] Understanding how the economic expertise perceives risks is becoming an essential topic for regulation.

Many historical studies suggest that the language of ‘risk’ was developed for the purpose of economic activities.[15] In the fields of finance and business management, risk is considered as a tool to facilitate individual decisions of economic activities. In this sense, ‘risk management’ often refers to the decision-making strategy of a firm or a person to evaluate risks, reduce costs and maximise profits.[16] Risk is thus embedded in the decision-making process, as ‘side effects’ of business activities to be managed. In fact, in Knight’s often cited work, risk was considered as something by definition manageable.[17] Knight made a clear distinction between ‘uncertainty’, those incalculable factors, and ‘risk’, which is calculable by methods of probability and statistic.[18] Moreover, the OECD also defines risk as ‘the measurable probability that the actual outcome will deviate from the expected outcome’.[19] Risk is ‘measurable’, and its impacts are potential deviations of outcomes, which link to companies’ efficiency.[20] Therefore, through probability and economic analysis, risk can be calculated and rationally managed, in order to reduce side effects and increase profits. In the language of business and finance, risk has a positive connotation.

This economic conceptualisation of risk, seeing risks as side-effects, calculable and potentially profitable, was originally operating predominantly in the private sector, but has entered into the modern practice of regulation.[21] It is therefore of key interest to explore the economic view of risk among experts in the context of risk regulation. This, as I will argue in the following paragraphs, can be analysed through examining the actual activities of risk communication between different groups of experts in relation to the process of standard-setting.

B. RISK COMMUNICATION AND RISK REGULATORY STANDARDS

In the risk regulation literature, risk communication is often defined as ‘an interactive process of exchange of information and opinion among individuals, groups and institutions’ that contains messages related directly or indirectly to risks.[22] Risk communication is thus a process that connects different actors, including scientists, regulators and the public, for the purpose of analysing and regulating risks.

In various models formulated by different studies about risk regulation, the role of risk communication is often a central one.[23] In fact, risk communication has gradually developed into an academic field of study in its own right, influenced firstly by experimental psychology and later on by sociology and cultural studies.[24] Some scholars stress that risk communication should not be perceived as merely transmission of information, and proposed that studies should aim at changing behavioural responses through ‘active’ risk communication or persuasion.[25] Many studies hence confine the study of risk communication to the relationships between the government and the public or those between regulators and regulated; they also concentrate on formulating guidelines or policy suggestions for communicating science and risk policies between the authorities and the lay public.[26] A significant strand of the risk communication literature is thus dominated by studies related to what I called expert-lay risk communication in a narrower sense, providing various strategies about how regulators can best ‘educate/persuade’ people, understand ‘lay perceptions’ and build ‘trust’ among the general public.

However, some scholars have noticed that this current trend of risk communication research has largely neglected the inter-expert dimension and underestimated the interactions ‘internally’ between scientists and regulators.[27] Being the core of risk regulation practice, risk communication should be studied in a broader sense, as ‘a constructive dialogue between all those involved in a particular debate about risk’.[28] This is also in line with the abovementioned classic definition of risk communication. Therefore, looking at risk communication can shed light on not only the discussion and evaluation of risks in policymaking, but also the formation of different ‘expert views’ toward risks. For the purpose of this paper, ‘risk communication’ should be understood specifically as the process of conceptualising risk through interactions between different actors, especially experts, in a risk regulatory regime. Inter-expert risk communication is therefore my unit of analysis to illustrate the key aspects of the economic view of risk in risk regulatory practice.

This empirical focus can be further narrowed down to the making of risk regulation standards as case studies. In a risk regulatory regime, the standard-setting process is where the evaluation of risk and the determination of the acceptability of risk take place. Standard-setting also provides an institutional context for the evaluation of risk, which is crucial to fully understand risk regulation.[29] Therefore, my analysis here will focus on inter-expert risk communication in relation to the process of standard-setting, which leads to my case study on the EMU fiscal rules.

III. EMU Fiscal Rules: A Case Study

The outbreak of the sovereign debt crisis in Greece in late 2009, later on escalated into the Eurozone crisis, has triggered highly scrutinised reviews of budgetary disciplines in the EU. The famous excessive deficit criteria, labelled here as the fiscal rules of the EMU, are standards triggering the Excessive Deficit Procedure laid down in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty and reaffirmed by the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and the European Council in 1997.[30] According to the Treaty text and its protocol, ‘Member States shall avoid excessive government deficits’ by following two criteria to maintain the ratio of government deficit to GDP under 3% and the ratio of government debt to GDP under 60%.[31] These two criteria (3% deficit, 60% debt) of the fiscal rules have become the benchmark for Eurozone countries to assess their budget deficits, and the cardinal standards for the EU to manage the risk of macroeconomic instability in the Eurozone.

Reasons for the fiscal rules to be an appropriate case to illustrate the economic view of risk are the following. Firstly, risks of economic instability were deemed as some ‘side effects’ associated with the creation of the EMU — they were by-products of the EMU, not some pre-existing hazards to be regulated. In this sense, managing ‘risks’ was an integrated part of the EMU project and the fiscal rules were tools of risk management, reflecting an economic view toward risks. Second, economics was undoubtedly the major source of expertise in the EMU debate. The analysis of the EMU project and the design of the fiscal rules relied mainly on the method of CBA.[32] The whole process of risk communication was heavily influenced by economists and experts in public finance. Finally, although the EMU debate was based on economic expertise, the scientific argument for the fiscal rules was rather simple.[33] This was already criticised by many academics in the 1990s, before the current Eurozone crisis.[34] In fact, most studies will agree that the EMU was after all a political project.[35] The ‘non-economic’ nature of monetary integration suggests that the fiscal rules have played a crucial role in shaping the complex debate between the economic expertise and politics.

Inextricably linked with the negotiation of the EMU, my analyses will concentrate on risk communication activities related to the fiscal rules that took place mainly from the 1989 Delors Report[36] and the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. Major actors contributed to the debate were the Monetary Committee (MC, replaced by the Economic and Finance Committee after 1999), the DG II (Economic and Financial Affairs) of the Commission, the Ecofin Council, the Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) on the monetary union, the Committee of Governors of Central Banks (CoG, the precursor of the European Central Bank) and several academics as external experts. A rich literature on the history and political economy of the EMU[37] has defined a relatively clear boundary for this case study and provided contexts and background for empirical analyses. My data include around 100 historical documents[38], 14 semi-structured interviews[39] and other publically available reports.[40] These materials were collated and coded in NVivo to discover patterns and themes related to risk communication, which I will discuss in the next section.

IV. The Politicisation of Economic Expertise in Risk Communication

The general theme of my findings is that economic expertise, through mobilising an economic view of risk, is politicised. This politicisation is a ‘process’[41] facilitated by inter-expert risk communication, and there are three dimensions: experts formulated a risk communication network that resembled a club; they shared a risk communication culture of optimism; and the results of risk communication, the EMU fiscal rues, were in fact arbitrary.

A. CLUB

‘Club’ is a key word that constantly emerges in my interviews and the literature. The discussion of the fiscal rules took place mainly in the MC, which was a specialised scientific body to provide expert opinions and to facilitate the process of economic and monetary integration.[42] There were two subgroups in the MC: the full members and the Alternates of members. Each Member State can nominate two full members, one from the national central banks and the other from the ministries of economics and/or finance, and two Alternates. The Commission can also send two members to the meetings. Members of the MC then elected a Chairman to represent the Committee, and a Chairman of the Alternates was also elected to represent the Alternates.

One predominant feature of this institutional setting is that there was a significant overlaps between memberships of the MC with other EU bodies, such as the IGC, the ECOFIN Council and the CoG. According to one official who participated in the discussion, members of the MC and those in the IGC meeting were actually the ‘same group of people’.[43] In fact, many other interviewees have indicated that the MC, the Alternates of the MC, the IGC, the secondary working group of the IGC, the ECOFIN Council, the CoG, and perhaps most importantly, the DG II of the Commission, were all closely related to each other.[44] This observation can be further confirmed by comparing the names recorded in various documents found in the two archives. Clearly, these people have created a tight-knit network at the EU level, and as several interviewees put explicitly, a closed club of European experts.[45]

This ‘clubby’ atmosphere was developed due to the common academic training and worldview that these experts shared,[46] and it has a power to transcend national boundaries, because ‘it’s the same kind of culture you grew up in whatever country you come from.’[47] Some other researchers also described the MC as an ‘Old Boys’ Club’[48], and emphasised the MC’s ability to deal with technical issues with political sensitivity through a highly secretive but intensive setting.[49] Experts participated in the decision-making process of the fiscal rules formulated a well-organised, confined and centralised ‘network’ — their memberships overlapped, and there was less distinction between technical and political bodies.

A club, in terms of social network analysis, can be described as ‘high centrality’ and ‘network closure’.[50] It creates a strong binding mechanism to facilitate coordination and communication.[51] In terms of its impact on risk communication activities, a club network can foster harmonious risk communication. ‘They tend to become friends’, as one expert who worked at a national ministry observed, ‘you don’t want to offend your colleagues. It was not so contentious.’[52] This does not mean that experts never disagree with each other, but it does imply that forging a common position has become less difficult. Moreover, a cohesive network provided an environment for intensive risk communication. The core discussion of the fiscal rules was conducted in a relatively short time period (especially when compared with the case of the 2-degree target), mainly from October 1989 to September 1991, and budgetary discipline was clearly a frequent topic.[53] In addition, a club can create a tendency of iterative risk communication. There was a multi-layered discussion between the IGC, the MC, the Alternates of the MC and the Commission, which constantly required confirmation and specification of technical details through expertise at different levels.[54] This kind of iterative risk communication practice was in fact part of the natural outcome of a harmonious and intensive discussion, in order to facilitate solid consensus. In short, a rapid and highly intensive discussion was guaranteed by the confidential, collegial environment and a sense of trust facilitated, through high centrality and network closure of the ‘euro club’.

One additional feature of this club network worth mentioning here is its stabilising mechanism. As discussed previously, members of the MC and those of the IGC participants were basically the same group of people. This special structure was constructed specifically for the purpose of political negotiation, as one expert explained:

The Maastricht criteria were not developed in the Monetary Committee (MC) proper. The MC existed and, for the purpose of the Treaty, converted itself into what was called the Intergovernmental Conference (IGC). […] They had this dual-role, so it was quite funny sometimes they were talking as the MC and then just change itself as the IGC. […] Because the MC was an advisory committee, whereas the IGC was a negotiating forum. They actually negotiated the Treaty there. I know this is a bit religious but that was a bottom-line: they could not negotiate the Treaty as the MC; they had to change themselves into [the IGC].[55]

The ‘dual-role’ of members of MC/IGC was thus justified by an artificial institutional setting. According to this institutional design of the Maastricht negotiation, the MC was supposed to be solely an advisory body, and the functions of decision-making and technical expertise should have been clearly separated.

The same official continued that the division of labour between the MC and the IGC was quite clear in formality, and the members were actually able to ‘talk about things as economists and then politically’ as well as to adopt different positions in different meetings. However, when asked about whether experts in the MC can really prevent the presentation of national interests, she stressed that the formats of discussion were different, but it was ‘just a way to legitimise the works here’. She said:

In fact, the MC has changed in that period. What it didn’t really manage that well was, it became less of a technical group, and more of a negotiation [one]; and even when the Treaty was over, and all the IGC was over, they were not quite the same MC [as before].[56]

These comments seem to suggest that there is an interactive relationship between the network structure and the process of risk communication. On the one hand, different institutional environments can influence how messages of risk are phrased (experts discussed things technically in the MC but negotiated politically in the IGC); on the other hand, the whole practice of risk communication can also eventually shape the nature of institutional environment (the actual process of Maastricht negotiation has turned the MC into a de facto political body).

The above observation is supported not only by some other officials who have participated in the discussion[57], but also several archival documents about ‘the role of the MC’ before the final rounds of negotiation of the Maastricht Treaty.[58] Therefore, although experts did seek to perform differently when they changed hats, the new institutional arrangement (the IGC/MC divide) became eventually inconsequential to the network structure. In other words, the attempt to separate economic expertise from political negotiation only generated some marginal effects on formality. The nature of the MC became more political, reflecting the reality of risk communication activities, and the experts remained connected closely in the same club. There appears to be a stabilising mechanism that ensures the structure of expert network reflects the actual practice of risk communication.

The economic view of risk considers risk as ‘something to be managed’ through the decision-making process. Risk management (including evaluation and allocation of risks) is integrated with policymaking. With an economic thinking of risk, experts tend not to distinguish economic expertise from policy decisions, and this was reinforced over time, turning into a closed club of expert network. A club network has led to harmonious, intensive and iterative practices of risk communication. This environment further contributed to another feature of the economic view of risk in risk communication — the optimistic culture.

B. OPTIMISM

The institutional structure of a club network not only influences risk communication behaviours, but also generates a certain ‘culture’. Defined as ‘a particular world of beliefs and practices associated with a specific group’,[59] the culture of economic expertise in terms of risk communication provides a helpful lens to understand the economic view of risk. The discussion of the EMU fiscal rules was particularly ‘optimistic’, and this can be understood in two perspectives: economic experts communicated risk with a ‘make-it-work’ mentality, and they conceptualised risk through a ‘positive framing’.

a. Make-it-work mentality

Experts who participated in the euro project tend to have strong beliefs in European integration in general and the EMU in particular. Some connected this belief in a personal, emotional way, like one economist who joined the team when the CoG was still based in Basel recalled:

Following the Delors Report, I went, with other people, to Basel. We moved to Basel with the feeling that we were starting a long journey toward the creation of a single currency. That was an absolutely exciting feeling. […] It was an extraordinary experience, because a new team of economist was set up, all detached from their own countries to work on a truly European project.[60]

The creation of the EMU was undoubtedly a great milestone of European integration. Almost every expert I interviewed showed their personal excitement about being part of a critical historical moment, and for many senior experts at that time, this belief was further enhanced by the political ideal that European integration was essentially a peace-keeping project:

These were people who remembered more about what we got in the war. I think that was a lot fresher, even for people who were heads of states at the political level, who were thinking more about what we have got in the past. There was a general feeling that we really need to do this (for peace-keeping), which has somehow been forgotten today. They were certainly much more committed.[61]

Therefore these experts, with their personal passion, fresh memories of the war and a sense of mission for the common good of Europe, also demonstrated some strong personalities in risk communication. Many interviewees, as junior officials in the back row, described the members of the MC and the IGC as ‘strong characters’ or ‘very powerful intellectuals’, and the meetings as ‘second education’.[62] Several names, among others Han Tietmeyer, Helmut Kohl, Jean-Claude Trichet, Nigel Wicks and Mario Draghi, were constantly mentioned by many interviewees as ‘big people’, but perhaps the key pusher of the EMU project was still the Commission:

The vision for an EMU was a vision held by our President, Jacques Delors. He was the strongest President that we have had, since then there was nobody like him. He drove the [EMU] as much as at the Commission level as at the Member States level. He was a very good negotiator, and he made sure that we had whatever we needed to carry the project through.[63]

From the President of the Commission to the Alternates of the MC, experts were highly determined to make the EMU project work. This ‘make-it-work’ mentality has turned risk communication into a result-driven process and sped up the discussion, as shown clearly in the reports and minutes of the MC before the eve of the Maastricht Summit:

As indicated at the last meeting, the Chairman considers that the meeting of 30 September has a special nature, in that the Committee has to reach agreement on the key points of the excessive-deficit procedure. A large area of common ground already exists.[64]

It explicitly stressed the importance of having a consensus before the deadline for the Maastricht Treaty. This 2-page note listed all ‘outstanding issues’ in a simplistic way, and proposed possible conclusions based on existing ‘common ground’. Clearly, efficiency was the primary concern here, and the official minutes of the MC also emphasised the critical role of the MC in the whole discussion about the risk and control of excessive deficits, in order to offer the guidance to the IGC.[65] In fact, the discussion was indeed guided with a very strong intension to ‘make things work’:

The Chairman began by re-emphasizing his view that it would be difficult to achieve EMU if an excessive deficits procedure were not defined in watertight terms. There could be no further delay in reaching agreement.[66]

Examples like this can be widely found, explicitly or implicitly, in historical records acquired from the two archives. Experts therefore shared a strong desire of achieving positive results out of risk communication, and this may be based on their personal experience, professional judgement or political belief. This make-it-work mentality has significantly accelerated the process of risk communication. Moreover, it echoes with the closed network discussed above — a club-like structure has cultivated a make-it-work mentality for intensive, iterative and harmonious discussion of risks.

b. Positive framing

The other cultural perspective of the economic view of risk is related to its positive connotation. The economic origin of risk coincides with the development of maritime trade, the discovery of probability theory, and the rise of modern capitalism.[67] In the world of finance, risk is often linked with ‘premium’. Insurance, as ‘a technology of risk’, sees risk as a form of ‘capital’.[68] The action of risk-taking is incentivised with profits, and it is argued that these rational choices of risks are driving our economies forward.[69]

A neutral or even slightly positive stance towards risk can be found in the literature of economics and finance.[70] Experts trained under this educational background therefore tend to view risk as a form of uncertainty with potential positive outcomes. This is also true for economists who were involved in the discussion of the EMU fiscal rules. ‘For me, risk means it can go one way, [and] it can go the other way.’ A senior expert who worked in the CoG expressed her view, and also added that all these talks about financial risk in a negative sense are ‘rather recent’. When further asked about the current discussion of financial risk, she commented: ‘I think it’s a bit like clean air. Nobody can be against sound public finance.’[71] For her, managing risk means achieving good results.

Constructing the control of risk as ensuring positive outcomes, rather than avoiding negative consequences, is a positive framing of risk. This might seem like just the flip side of the same coin. However, different points of departure of risk communication may have an impact on how risk is further discussed, because positive framing denotes a sense of ‘optimism’. This is not at all surprising if we take the above mentioned ‘make-it-work’ mentality into account. In order to realise monetary integration, the hidden assumption in risk communication of the EMU was that economic and monetary stability can be achieved, the only problem was how. The big question behind the discussion of the fiscal rules was not how to avoid danger or problems caused by the EMU (negative framing), but how to maintain sound budgetary policies in the EMU (positive framing).

Therefore, different concepts of risks related to the creation of the EMU were captured through the notion of sound economic and monetary policies. The SGP defines ‘the objective of sound government finances as a means of strengthening the conditions for price stability and for strong sustainable growth conducive to employment creation’.[72] Sound public finance, stability and sustainability have thus become the key concepts that guided the discussion of the EMU and the fiscal rules. Using these terms has signified a positive framing of risk.

For example, in the 1989 Delors Report, it was suggested that in the economic field of the monetary integration, the Community should ‘impose constraints on national budgets to the extent to which this was necessary to prevent imbalances that might threaten monetary stability’.[73] The Commission, in its famous ‘One market, one money’ report backing the EMU project, also reaffirmed the need for fiscal discipline and iterated several times the importance of budgetary sustainability and price stability.[74] Not to mention in the MC, the two criteria of the fiscal rules were named as the ‘unsustainability criterion’ (on debt ratio) and the ‘economic instability criterion’ (on deficit ratio):

The [Monetary] Committee considered a spectrum ranging from imminent default through unsustainable snowballing of debt, and various ways in which monetary stability might be endangered, to inappropriate policy mixes and overheating. They concluded that two types of danger are relevant in this context:

a) deficits producing unsustainable stocks of public debt […];

b) deficits of a size that could endanger monetary stability […].[75]

The above quote from the MC report is a perfect example to demonstrate what ‘positive framing’ of risk actually means. It does not mean that experts did not use any negative term during the discussion. Quite the contrary, as shown in the text above, communications between experts about the EMU and the need of fiscal rules were indeed about problems and caveats. However, these negative issues are debated in a wider context of ensuring sustainability, stability and sound money policy. A positive framing of risk set the agenda of the EMU debate in an optimistic direction, which echoes the make-it-work mentality of the experts. Hence, potential danger of excessive deficits and methods to prevent them were always understood in relation to ensuring sustainability and stability in the EMU. Numerous examples can be extracted from the reports and minutes of the MC, the Commission and the CoG, using terms such as ‘instability’, ‘unsustainability’, ‘asymmetry’ and ‘imbalance’ to evaluate fiscal rules. The discussion of excessive deficits was embedded within the maximisation of the opportunities of the EMU, as one senior expert who witnessed the debate acutely pointed out:

[We] tended to think in positive terms, but we were talking about imbalance, we were talking about danger, […] we probably use the term risk, but as we always say, any risk entails an opportunity. We took a calculated risk, and we believed that the common currency would create a dynamic, that would lead Europe [forward]. That was really the view. So risk yes, but opportunity.[76]

C. ARBITRARINESS

The optimistic culture among experts, understood as the make-it-work mentality and the positive-framing of risk, together with the closed club network have led to some curious consequences. The EMU fiscal rules were based on economic expertise, yet the economic rationale behind the rules is often criticised.[77] The outcomes of risk communication are ‘arbitrary’ because they were not strictly scientific and created some regulatory blind spots. However, this arbitrariness was not ‘random’ — it was actually based on ‘strategic’ choices of economic experts in the process of risk communication.

The ‘arbitrariness’ of the fiscal rules need to be understood firstly as results of narrowly focused discussion, as an economist of the CoG commented: ‘the risk at the time, as it was perceived, was focusing on public finance, per se’[78]. Through risk communication, wider concepts of macroeconomic risks in the EMU were confined to sound public finances, or more specifically, avoiding excessive deficits. Many interviewees reflected critically that focusing on budgetary deficits was eventually ‘too narrow’ and causing many regulatory ‘blind spots’, such as neglecting the problems of competitiveness in peripheral countries and the contagion effect from the private sector.[79] Several studies have suggested that the overly narrowed fiscal rules and these blind spots had led to the Eurozone crisis.[80]

This practice of narrowing down ‘risks’ to issues of public finance is in fact rooted in earlier attempts of European monetary integration. The emphasis of coordinating economic and budgetary policies is historically rooted in the debate between the monetarist and the economist schools of European monetary integration.[81] The ‘monetarists’, supported mainly by France, saw a monetary union as a key driving force for European integration, whereas the ‘economists’, influenced by Germany, emphasised the importance in converging economic performances before establishing a monetary union.[82] This monetarist-economist debate defined the basic language of EMU discussion to focus on the area of public finance. Against the background of European integration and the make-it-work mentality, concepts of coordinating fiscal policies and converging different economic performances were thus developed as compromises of this historical debate.

Coordination and convergence were the two key concepts mobilised to narrow down the scope of risk discussion. ‘Greater convergence of economic performance is needed’, the Delors Report has stated clearly, that a monetary union will ‘necessitate a more effective coordination of policy between separate national authorities’.[83] Moreover, an annex of the Delors Report had explicitly set fiscal coordination as the central method of achieving a sustainable monetary union.[84] In fact, after analysing the archival data and comparing the code sets between stability/sustainability and coordination/convergence, the results shows a strong relationship between these two sets of concepts. Coordination and convergence were therefore considered as key approaches to maintain sound money policy, stability and sustainability. An overzealous concentration on ‘convergence’ has drifted away from scientific risk analysis and caused serious biases, as a senior official in the Commission recalled the rationale behind the EMU fiscal rules discussion:

I will say that it doesn’t matter what you converge to as long as you converge to it. That was the point. The point was not the number; the point was the convergence.[85]

In fact, the emphasis on convergence/coordination in the EMU was about converging to a number, not about converging to the best number (which, as many economists will argue, may not exist), nor about how to converge. A comment from another expert worked in the Commission at the time further support this argument:

There was a focus on nominal convergence criteria rather than real convergence criteria, because it was felt that nominal will be sufficient rather than asking for real convergence…. [One] could not focus too much on those real issues.[86]

Through the language of convergence, macroeconomic risks of the Eurozone were radically narrowed down to the risk of excessive deficits, led to the creation of the fiscal rules. This process has left many risks unrecognised: ‘we were aware of some risks, but we were not fully aware of the others,’ and created several ‘analytical blind spots.’[87]

Although this paper does not intend to discuss the cause of Eurozone crisis, pointing out the source of these blind spots, due to overly narrowed discussion, help explain why so many experts viewed the EMU fiscal rules critically with hindsight:

The 60% [rule] was quite simple and very unscientific, because that was the average [debt level of Member States] at that time. Yes, there was a debate like should it be higher or lower, […] but we couldn’t agree on anything else basically.[88]

The 60% debt criterion was actually the initial proposal of the Commission early in the debate.[89] Therefore, interestingly, it has become simultaneously the initial position for discussion and the bottom line of compromise. This figure might not be particularly reasonable, but there was no other more reasonable alternative either. In fact, the 60% debt level of the Community was also part of the economic rationale for the 3% deficit level, as one expert who took part in the MC debate explained, again in a rather critical tone:

There is no optimal level of public debt in theory. There is no optimal level of deficit either. So what happened was at some meetings in the 90s, they did the kind of Sargent-Wallace calculation: growth in Europe, study says, was about 3%; stable inflation was defined as 2%; that makes long-term interest rate a number of 5[%]; the average debt ratio was 60[%] — they just reverse-engineered through the calculation to get 3[%]. So there was nothing economic about 3 and 60. […] It wasn’t that reasonable. It was not scientific. It was arithmetic. It came from the present monetary arithmetic, unfortunately.[90]

Is ‘arithmetic’ arbitrary? According to the minutes of the MC, many experts had shown their concern about the arbitrariness of the rules; yet interestingly, while some found the figures arbitrary and unacceptable, others favoured these figures because they were arbitrary.[91] In other words, it was not that experts did not see the arbitrariness of the rules. On the contrary, they tried to use such arbitrariness in a ‘strategic’ manner. One example is the debate about having ‘simple’ rules, as the minutes of the MC noted:

The majority of delegates in favour of the benchmark approach supported simple indicators as these would be most easily understood by politicians and the general public, and were in any case only providing an initial screening. Others argued that this screening needed to be as accurate as possible to avoid both wasting time and political embarrassment, and hence if complexity was needed, then so be it.[92]

Note that this discussion took place in the Alternates’ meeting, which was supposed to be purely ‘technical’. However, it seems quite clear that their discussion about whether the fiscal rules should be ‘simple’ or not had gone beyond the economic rationale and become quite ‘political’. Similar discussions actually appeared several times before and after this particular meeting.[93]

In the end, simple rules prevailed. The strategic choice of arbitrary rules was part of the political compromise. Economic expertise, in this sense, should perhaps be more than just providing economic analyses, as an expert commented:

Even though we were fully aware that this was arbitrary [we still need a rule]. I mean the question is that human being, being as what they are, and the politicians being what they are… perhaps technocrats conspired to create a rule, however arbitrary, but that would tie the hands of politicians. […] The arbitrary rule might be preferable than no rule.[94]

The role of economic expertise in the EMU fiscal rules debate was therefore much more complex than conducting scientific assessments and giving professional advices. They are in a special position to create arbitrary rules that reflect political judgements. Many experts have acknowledged the arbitrariness of the fiscal rules, but they also, somewhat paradoxically, considered the rules ‘reasonable’.[95] The fiscal rules may be arbitrary (due to its overly narrowed focus and thin arithmetic foundation), but they were chosen strategically by experts (based on technical consensus reflecting political compromises).

V. Conclusion: The Art of Arbitrariness

By examining the expert debate about the fiscal rules, my case study demonstrates how economic expertise and the economic view of risk operate in inter-expert risk communication. The risk communication network can be described as a club, with economic experts integrated in the wider policymaking circle. Economic experts further adopted an optimistic culture, framing risks in a positive way and discussing risks with a make-it-work mentality. The results of inter-expert risk communication were therefore arbitrary, but such arbitrariness should be understood as part of the strategic choice of economic expertise. The club network, the optimistic culture and the strategic arbitrary outcomes are three different but interconnected aspects of risk communication among economic experts.

While mobilising economic expertise is the ‘art of government’, communicating risks with an ‘economic’ conception can be understood as the ‘art of arbitrariness’. ‘Risk’ in an economic view may be uncertain, but they are considered calculable and as part of the process toward positive results. Economic experts, at least in the case of the EMU negotiation, provide technical inputs that are mixed with political judgements. However, it is unfair to say that these experts were not ‘professional’ simply because of the fiscal rules were politicised:

It was not that we did not see risks or debate risks. It was mainly I think, on certain point, we misjudged. It was an error in judgement when it came to certain risks of the risk assessment. […] It was definitely not that everybody wanted the euro and you just go for it. That’s definitely not the case.[96]

Judgements of economic experts were shaped by the club network and the optimistic culture, but experts still sought to discuss the inevitable arbitrary rules strategically. Against the background of the Eurozone crisis, it is of particular interest to ask how we can avoid ‘misjudgements’ again. My paper may not provide a direct policy suggestion, but the important questions that emerge from it are: who should make judgements and how judgements should be made. These are questions of institutional design: Is the current ‘club’ structure best for mobilising economic expertise in risk regulation? Should the ‘optimistic culture’ of economic view be adjusted? What can be done to improve the ‘strategic’ element of the arbitrary risk regulation standards? These issues require further studies of the role of economic expertise in risk regulation and comparing the ‘economic view’ of risk to other conceptualisations of risk in those conventional risk regulatory regimes.

Image ‘Historical Archives of the European Commission’ by Po-Hsiang Ou.

[1] DPhil candidate, Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, University of Oxford. An earlier draft of this paper was presented in the ECPR Graduate Student Conference in Innsbruck, July 2014. I am very grateful for the feedback received at the conference and the helpful comments from the reviewers. I also thank the Historical Archives of the European Central Bank and the Historical Archives of the European Commission for assisting my data collection ([email protected]).

[2] Andre Szasz, The Road to European Monetary Union (Palgrave Macmillan 1999) xiii.

[3] Elizabeth Fisher, ‘Risk Regulatory Concepts and the Law’, in OECD (ed) Risk and Regulatory Policy: Improving the Governance of Risk (OECD 2010) 45.

[4] Christopher Hood, Henry Rothstein and Robert Baldwin, The Government of Risk: Understanding Risk Regulation Regimes (Oxford University Press 2001).

[5] John Graham, ‘Making Sense of Risk’ (2000) 20 Risk Analysis 302.

[6] Robert Kennedy, ‘Risk, Democracy and the Environment’ (2000) 20 Risk Analysis 306.

[7] Elizabeth Fisher, Risk Regulation and Administrative Constitutionalism (Hart Publishing 2007) 11–17.

[8] My definition of ‘experts’ here is therefore a broader one: it includes not only ‘technical experts’, such as scientists, economists and other academics, but also those ‘specialised policymakers’, who have a certain degree of specific expertise and communicate actively with technical experts.

[9] Mitchell Dean, Governmentality: Power and Rule in Modern Society (SAGE Publications 1999) 16-18.

[10] ibid 19; Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon and Peter Miller, The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality (1 edition, University Of Chicago Press 1991) 14–27.

[11] Richard A Posner, Catastrophe: Risk and Response (OUP 2004).

[12] William D Schulze and Allen V Kneese, ‘Risk in Benefit-Cost Analysis’ (1981) 1 Risk Analysis 81.

[13] For example: Bettina Lange, Implementing EU Pollution Control: Law and Integration (CUP 2008); Fisher (n 7); Alberto Alemanno, Trade in Food: Regulatory and Judicial Approaches to Food Risks in the EC and the WTO (Cameron May 2007); Scott Lash, Bronislaw Szerszynski and Brian Wynne (eds), Risk, Environment and Modernity: Towards a New Ecology (SAGE 1996).Fisher (n 6). The body of literature in risk regulation is massive and this is clearly not an exhaustive list. However, it should be noted that the field of ‘risk regulation’ also covers other issues that are not strictly linked to the use of ‘new’ technologies, such as natural disasters, lifestyle risks and road safety.

[14] Bettina Lange and Dania Thomas (eds), From Economy to Society? Perspectives on Transnational Risk Regulation (Emerald 2013).

[15] Peter L Bernstein, Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk (New Ed, John Wiley & Sons 1998); Vincent T Covello and Jeryl Mumpower, ‘Risk Analysis and Risk Management: An Historical Perspective’ (1985) 5 Risk Analysis 103.

[16] Aswath Damodaran, Strategic Risk Taking: A Framework for Risk Management (Wharton School Pub 2008) ch 1.

[17] Frank H Knight, Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit (Houghton Mifflin Company 1921).

[18] ibid.

[19] OECD, Public-Private Partnerships: In Pursuit of Risk Sharing and Value for Money (OECD 2008) 48.

[20] ibid 48–49.

[21] This is sometimes presented as ‘risk-based regulation’ or ‘new public risk management’: Julia Black, ‘The Emergence of Risk-Based Regulation and the New Public Management in the United Kingdom’ (2005) 2005 Public Law 512; Michael Power, Organized Uncertainty: Designing a World of Risk Management (OUP 2007).

[22] National Research Council, Improving Risk Communication (National Academies Press 1989) 21.

[23] For example: Renn (n 5); Alemanno (n 12); Gregory Bounds, ‘Challenges to Designing Regulatory Policy Framework to Manage Risks’, in OECD (ed), Risk and Regulatory Policy: Improving the Governance of Risk (OECD 2010) 15.

[24] Ragnar E Lofstedt, ‘Risk Communication and Management in the 21st Century’ (2004) 7 International Public Management Journal 335.

[25] Carlo C Jaeger and others, Risk, Uncertainty and Rational Action (Routledge 2001) 127–129.

[26] For example: Renn (n 23) 242; Paul Slovic, ‘Perceived Risk, Trust, and Democracy’ (1993) 13 Risk Analysis 675; W Leiss, ‘Three Phases in the Evolution of Risk Communication Practice’ [1996] The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 85; B Fischhoff, ‘Risk Perception and Communication Unplugged: Twenty Years of Process’ (1995) 15 Risk Analysis 137; Ragnar EE Lofstedt, Risk Management in Post-Trust Societies (Earthscan 2012).

[27] Renn (n 23) 202.

[28] Ragnar E Lofstedt, ‘How Can We Make Food Risk Communication Better: Where Are We and Where Are We Going?’ (2006) 9 Journal of Risk Research 869, 871.

[29] Fisher (n 3); Bronwen Morgan and Karen Yeung, An Introduction to Law and Regulation: Text and Materials (Cambridge University Press 2007).

[30] European Council, ‘Resolutions of the European Council on the Stability and Growth Pact’, Amsterdam, 16-17 June 1997.

[31] Art 126 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU, ex Art 104 TEC) and the Protocol (No 12) on the Excessive Deficit Procedure.

[32] Commission, ‘One market, one money: An evaluation of the potential benefits and costs of forming an economic and monetary union’, European Economy No 44, Brussels, October 1990; Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union (ed), Collections of papers submitted to the Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union (European Communities 1989).

[33] 60% public debt was the average figure of the European Community in 1990. In order to at least maintain such debt ratio, under the condition of 2% inflation rate and the assumption of 3% annual growth in GDP, the tolerable deficit is then 3% of GDP. Jan Viebig, Der Vertrag von Maastricht: Die Positionen Deutschlands Und Frankreichs Zur Europäischen Wirtschafts- Und Währungsunion (Schäffer-Poeschel 1999) 355–364; Daniel Gros and Niels Thygesen, European Monetary Integration: From the European Monetary System to Economic and Monetary Union (2nd edn, Longman 1998) 340.

[34] Jose Vinals, ‘Building a Monetary Union in Europe: Is It Worthwhile, Where Do We Stand, and Where Are We Going?’ (Centre for Economic Policy Research 1994) CEPR Occasional Paper No. 15; Barry J Eichengreen, Should the Maastricht Treaty Be Saved? (Princeton Univ Intl Economics 1992); David Begg and others, The Making of Monetary Union: Monitoring European Integration (CEPR 1991).

[35] Two books written by former central bankers who participated in the EMU project are particular insightful: Andre Szasz, The Road to European Monetary Union (Palgrave Macmillan 1999); Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa, The Road to Monetary Union in Europe: The Emperor, the Kings, and the Genies (2nd Revised edition, OUP Oxford 2000); for a much more radical critique from a former Eurocrat: Bernard Connolly, The Rotten Heart of Europe (Faber & Faber 2013).

[36] Committee for the Study of Economic and Monetary Union, ‘Report on economic and monetary union in the European Community’ (Delors Report, European Communities 1989).

[37] On top of the sources listed in footnote 35, see also Harold James, Making the European Monetary Union (Belknap Press 2012); David Marsh, The Euro: The Battle for the New Global Currency (Yale University Press 2011); Kenneth Dyson and Kevin Featherstone, The Road to Maastricht: Negotiating Economic and Monetary Union (Oxford University Press 1999).

[38] The archival data came mainly from two sources: the Historical Archives of the Commission and the European Central Bank Historical Archives. It is however difficult to count the exact number of documents acquired because there are many repeated copies of draft reports and minutes, as well as reports with multiple annexes.

[39] For the purpose of anonymity interviews are cited in this paper as ‘fake initials’.

[40] Such as the Delors Report, the Commission communications and reports made by the ECB.

[41] Pieter De Wilde, ‘No Polity for Old Politics? A Framework for Analyzing the Politicization of European Integration’ (2011) 33 Journal of European Integration 559.

[42] Age FP Bakker, The Liberalization of Capital Movements in Europe: The Monetary Committee and Financial Integration, 1958-1994 (1st edn, Springer 1995) ch 4. This is also supported by many interviews: interviews with NM (Brussels, 16 April 2013), NS (Frankfurt, 8 April 2013) and PQ (Frankfurt, 8 April 2013).

[43] Interview with JC (Brussels, 16 Apr 2013).

[44] Interviews with NS (Frankfurt, 8 April 2013), NM (Brussels, 16 April 2013), CS (Louvain-la-Neuve, 27 June 2013), HG (Copenhagen, 27 August 2013) and HR (Brussels, 4 April 2014).

[45] Interviews with JC (Brussels 16 Apr 2013), CS (Louvain-la-Neuve, 27 Jun 2013) and HG (Copenhagen, 27 Aug 2013).

[46] As one senior official commented, experts at this European level share not merely a common background in economics, but a highly similar ‘German-style’ economic thinking. Interview with HR (Brussels, 4 April 2014).

[47] Interview with HG (Copenhagen, 27 Aug 2013).

[48] Amy Verdun, ‘Governing by Committee: The Case of Monetary Policy’ (EU Center of California Working Paper 1999).

[49] ibid; Bakker (n 42).

[50] Stephen P Borgatti and others, ‘Network Analysis in the Social Sciences’ (2009) 323 Science 892; Ronald S Burt, ‘The Network Structure of Social Capital’ (2000) 22 Research in Organizational Behavior 345.

[51] Borgatti and others (n 50).

[52] Interview with CS (Louvain-la-Neuve 27 Jun 2013).

[53] During this period of less than two years, the MC has organised 28 meetings, and 12 meeting were noted with high relevance to the discussion of the fiscal rules. This number however does not include meetings with lower relevance, or those meetings of the Alternates and the IGC working groups.

[54] For example, out of 33 documents identified as highly relevant to the discussion of the fiscal rules, 18 of them explicitly required certain technical issues to be confirmed or specified in other bodies.

[55] Interview with JC (Brussels, 16 Apr 2013).

[56] ibid.

[57] Interviews with NM (Brussels, 16 Apr 2013) and KK (Brussels, 27 Jun 2013).

[58] For example: Commission, ‘Short Minutes of Monetary Committee 13 March 1991’ (II/01624 of 15 March 1991), section 4; Monetary Committee, ‘Priorities for the Monetary Committee in the Post-Maastricht Era’ (MC/II/19/92-EN of 17 January 1992).

[59] Susan S Silbey, ‘Legal Culture and Cultures of Legality’ in John R Hall, Laura Grindstaff and Ming-Cheng Lo (eds), Handbook of Cultural Sociology (Routledge 2010) 470.

[60] Interview with PQ (Frankfurt, 8 April 2013).

[61] Interview with NM (Brussels, 16 April 2013).

[62] Interviews with JC (Brussels, 16 April 2013) and NM (Brussels, 16 April 2013).

[63] Interview with NM (Brussels, 16 April 2013).

[64] Monetary Committee, Secretariat, ‘Outstanding issues on the excessive-deficit procedure’, Brussels, 20 September 1991 (emphasis added).

[65] Monetary Committee, Secretariat, ‘Draft minutes of the 383th meeting’, Brussels, 3 September 1991 (MC/II/392/91-EN).

[66] Commission, ‘Short minutes of Monetary Committee, 30 September 1991’, Brussels, 4 October 1991 (II/05112), 3.

[67] Bernstein (n 15); Covello and Mumpower (n 15).

[68] Burchell, Gordon and Miller (n 10) 197.

[69] Bernstein (n 15).

[70] Damodaran (n 16); Knight (n 17).

[71] Interview with NS (Frankfurt, 8 April 2013).

[72] Council Regulation (EC) No 1467/97, Preamble para (2).

[73] Delors Report, para 59.

[74] Commission (n 32).

[75] MC, ‘Criteria for Excessive Deficits (1)’, Brussels, 25 February 1991, 3-4.

[76] Interview with CS (Louvain-la-Neuve, 27 June 2013).

[77] Willem Buiter and others, ‘Excessive Deficits: Sense and Nonsense in the Treaty of Maastricht’ [1993] Economic Policy 58.

[78] Interview with NS (Frankfurt, 8 Apr 2013).

[79] Interviews with NW (Oxford, 16 January 2013), NM (Brussels, 16 April 2013), CS (Louvain-la-Neuve, 27 June 2013), LQ (Brussels, 27 Jun 2013) and KK (Brussels, 27 June 2013)

[80] David Marsh, Europe’s Deadlock: How the Euro Crisis Could Be Solved – and Why It Won’t Happen (Yale University Press 2013); Matthew Lynn, Bust: Greece, the Euro and the Sovereign Debt Crisis (1 edition, Bloomberg Press 2010).

[81] Ivo Maes, ‘On the Origins of the Franco-German EMU Controversies’ (NBB 2002) National Bank of Belgium Working Paper 34.

[82] ibid.

[83] Delors Report, paras 10-11.

[84] Alexandre Lamfalussy, ‘Macro-coordination of fiscal policies in an economic and monetary union in Europe’ in Delors Report, Collection of papers (January 1989) 91.

[85] Interview with JC (Brussels, 16 April 2013).

[86] Interview with NM (Brussels, 16 April 2013).

[87] Interview with LQ (Brussels, 27 June 2013).

[88] Interview with HG (Copenhagen, 27 August 2013).

[89] Commission, ‘Criteria for excessive deficit: applications of real world examples’, Brussels, 7 February 1991 (II/56/91-EN).

[90] Interview with JC (Brussels, 16 April 2013).

[91] Commission, ‘Monetary Committee Meeting of 22 January’, Brussels, 24 January 1990; MC, ‘Draft minutes of the 380th meeting of the Monetary Committee’, Brussels, 18 February 1991; MC, ‘Outstanding issues of the excessive-deficit procedure’, Brussels, 20 September 1991.

[92] Nigel Jenkinson, ‘Criteria for Excessive Public Sector Deficits in Stag Three of EMU (Monetary Committee Alternates Meeting 15th November)’, 20 November 1990, 3 (emphasis added).

[93] Commission, ‘Monetary Committee Meeting of 22 January’, 24 January 1990; MC, ‘Draft minutes of the 380th meeting of the Monetary Committee’, Brussels, 18 February 1991; MC, ‘Outstanding issues of the excessive-deficit procedure’, Brussels, 20 September 1991.

[94] Interview with CS (Louvain-la-Neuve, 27 June 2013).

[95] Interviews with MT (Copenhagen, 27 August 2013), HG (Copenhagen, 27 August 2013) NS (Frankfurt, 8 April 2013), CS (Louvain-la-Neuve, 27 June 2013) and HR (Brussels, 4 April 2014).

[96] Interview with HG (Copenhagen, 27 August 2013).

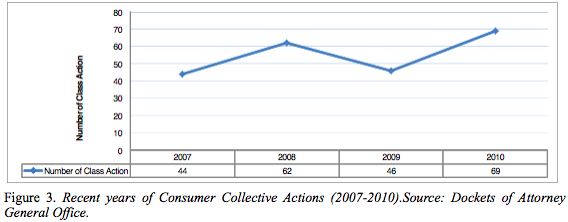

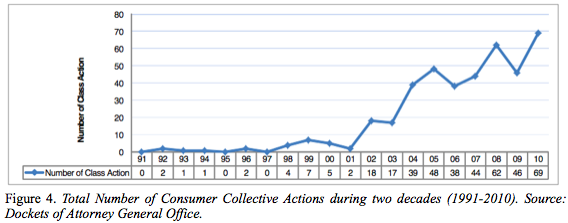

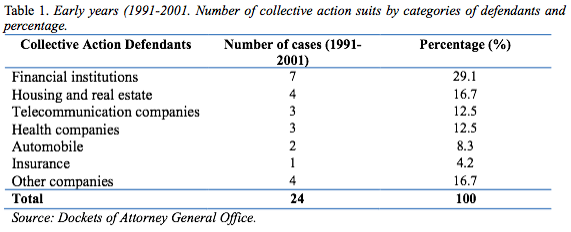

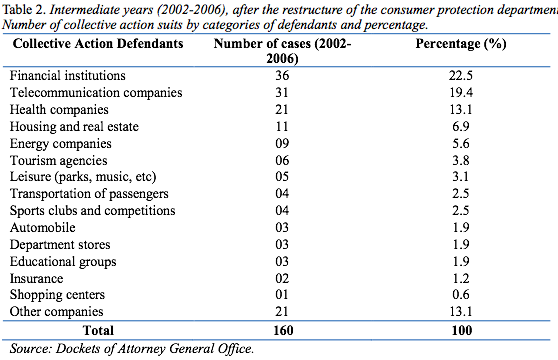

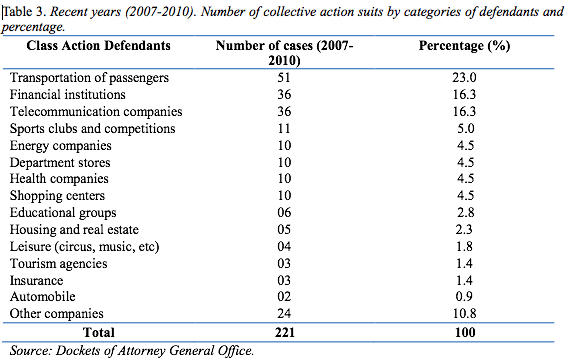

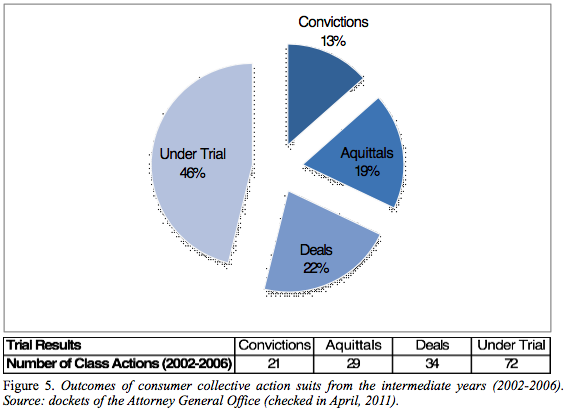

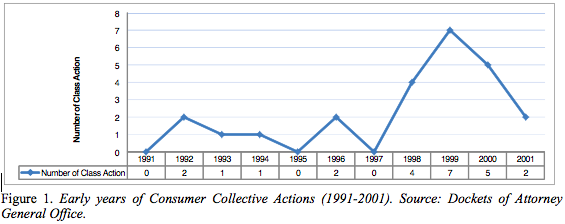

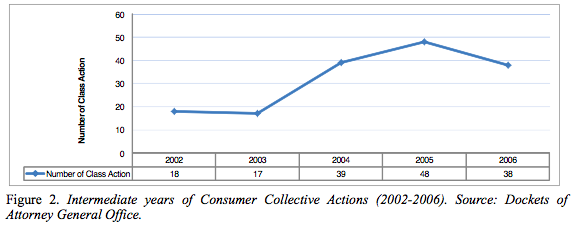

The Attorney General Office of Rio de Janeiro restructured its consumer protection department in 2001, appointing four independent prosecutors, whose investigations, deals, and litigation activities were not under the direct control of the Attorney General. Independence enhanced productivity, as it was no longer necessary to seek hierarchical approval or to worry about the political consequences of suing private companies. In addition, the necessary structure to conduct civil investigations was finally provided and more detailed evidence was collected to support collective actions. The appointment of four independent prosecutors for permanent positions also brought technical expertise since their growing experience and credence gradually improved the quality of their work and the quantity of collective actions filed. As a consequence, the consumer protection prosecutors filed 160 consumer collective actions against private companies within the following five years.

The Attorney General Office of Rio de Janeiro restructured its consumer protection department in 2001, appointing four independent prosecutors, whose investigations, deals, and litigation activities were not under the direct control of the Attorney General. Independence enhanced productivity, as it was no longer necessary to seek hierarchical approval or to worry about the political consequences of suing private companies. In addition, the necessary structure to conduct civil investigations was finally provided and more detailed evidence was collected to support collective actions. The appointment of four independent prosecutors for permanent positions also brought technical expertise since their growing experience and credence gradually improved the quality of their work and the quantity of collective actions filed. As a consequence, the consumer protection prosecutors filed 160 consumer collective actions against private companies within the following five years.