Cristina Golomoz[1]

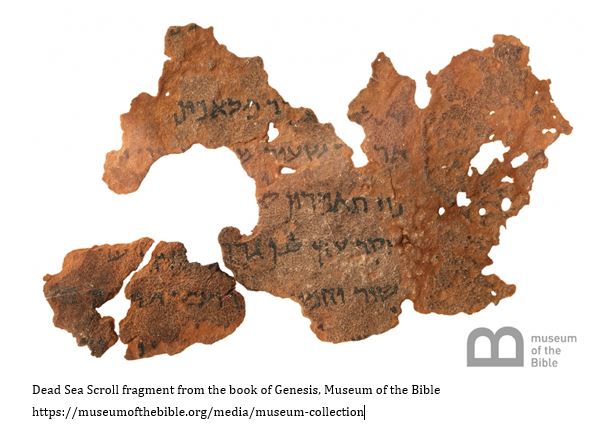

Can one truly own the Bible? Looking at the impressive collection of biblical materials to be put on display at the forthcoming ‘Museum of the Bible’ the answer would appear to be a resounding ‘Yes!’ The Museum of the Bible will open in Washington, D.C., in November 2017. It will house one of the biggest collections of biblical texts in the world, including rare manuscripts and books such as Dead Sea Scroll fragments, the first editions of the King James Bible, and fragments from the Gutenberg Bible.[2] The museum’s exhibition space is set to be 20 percent larger than Tate Modern’s in London – an impressive figure which reflects the project’s ‘biblical’ proportions.

The project’s mastermind is David Green, an American businessman who founded Hobby Lobby, an arts and crafts chain based in Oklahoma City. Hobby Lobby is well-known for its victory in a Supreme Court case in 2014 in which it sought exemption from paying insurance that covered contraception for employees on religious grounds. The Green family are evangelical Christians who have long dedicated their time, effort, and money to religious education and dissemination projects.[3] The Museum of the Bible is the most recent cause they have devoted themselves to in an attempt to ‘convey the global impact and compelling history of the Bible in a unique and powerful way.’[4]

Another cause sponsored by the Green family is the so-called ‘Scholars Initiative.’ This is a programme which supports scholarly research into the rare biblical texts owned by the Green family as part of the ‘Green Collection’, which will feature in the soon-to-be Museum’s exhibitions. Not only does this programme facilitate scholars’ access to previously unstudied material, but also to generous research funding and cutting-edge technologies used in this type of research. A veritable scholar’s paradise. But, according to some critics, there is a catch. Whilst officially there is ‘no religious requirement for involvement’, the institutions affiliated with the Green Scholars Initiative are almost all explicitly Christian, predominantly of the evangelical denomination.[5] Steve Green, David Green’s son and the chairman of the Scholars Initiative, explains how the scholars’ selection process is construed: they favour those researchers who ‘seek after facts’ and avoid those who are ‘antagonistic and are going to come to a conclusion that this book [the Bible] is not what it claims to be.’[6]

This approach to scholarly research has been widely criticised as a way to restrict the access of certain researchers to the biblical texts included in the Green Collection.[7] Furthermore, critics have also argued that this approach reflects a particular understanding of what the Bible is, which is grounded in the Green family’s evangelical faith.[8] Specifically, a vision of the Bible which stresses the text’s consistency throughout history and geographical contexts, and seeks to eliminate any contradictions within or fragmentation of the text. An illustration of this is provided in the description of the Museum’s mission: ‘to bring to life the living word of God, to tell its compelling story of preservation, and to inspire confidence in the absolute authority and reliability of the Bible.’[9] Such an understanding, it has been argued, fails to recognise the commonly held scholarly position that the Bible cannot be traced back to one single original text.[10] Rather, most historic theologians argue that it is a collection of texts and fragments upon which the passage of time and a great many complex socio-political contexts – such as the breakup of the Roman Empire or the Reformation, to mention just two well-known examples – have left their mark. Avoiding those scholars who ‘are going to come to a conclusion that this book is not what it claims to be’ does not appear to account for the ways in which ideology, interpretation, contradiction, and randomness have been incorporated in the biblical text as we today know it.[11]

Even though they are the owners of one of the largest private collections of biblical objects and artefacts in the world, the Greens like to describe themselves as ‘storytellers’ and ‘educators’, rather than ‘collectors.’[12] In Steve Green’s own words, the Scholars Initiative and the Museum aim to ‘tell the story of the Bible.’[13] This statement is perhaps an indication of just how far the Greens’ claim over the manner in which the meaning of the biblical text is transmitted reaches. By telling the story of the biblical artefacts and objects included in their collection, the Greens aspire to represent the Bible itself.

The fact that they own these rare objects is not without importance here. Being the owners of this collection has enabled them to control not only which researchers are selected onto their Scholars Initiative, but also the questions that are asked and the interpretations that are given to those biblical fragments. The insistence that we are presented with ‘simply the facts’ reads as an explicit attempt to legitimise the Greens’ vision of the Bible as true, or ‘factual’, whilst censoring alternative interpretations. This has the potential to influence not only what the millions of people who will visit the Museum learn about the Bible, but also how we understand the history of Christianity more generally.

That the Green family will control access to and the interpretation of the biblical material in its possession then raises the interesting question about what can and cannot be owned privately. What is the line of demarcation, and how rigid is it? The Greens own a collection of rare biblical artefacts, but can they be said to own the Bible? Surely, most would say that they do not. To take another example, we can imagine a situation in which a fragment of the original copy of the 1787 US Constitution comes into private hands. Yet, we would be reluctant to think that the US Constitution can be privately owned. What is the basis of this reluctance? There is no explicit rule of law that excludes the Constitution or the Bible from the things that can be privately appropriated. The Constitution and the Bible are intangible things, unlike the paper on which their texts are written. Yet, many intangible things can indeed be privately owned, such as a song, an invention, or a brand.[14] What, then, makes the idea of owning the Constitution or the Bible so inconceivable?

In the case of the Constitution, anthropologist Maurice Godelier argued that the inconceivability of ownership is grounded in the understanding that the principles and ideals expressed in this text are the ‘common property’ of the collective body of citizens.[15] In other words, the Constitution is thought to belong to each and every citizen by virtue of their citizenship – not by the simple virtue of possessing some tangible object. What sort of rights might such a notion of ‘common property’ involve? A possible answer is provided by Macpherson, who suggests that common property could entail a guarantee against being excluded from the use or benefit of a thing.[16] This contrasts with private property, which gives one the right to exclude others from the use or benefit of something. An example of a good which the state might declare for common use is a town park. If governed by a common property regime (also known as ‘the commons’), then the park would be considered non-transferable to a private owner.

In the context of Western legal systems, the idea of excluding certain categories of things from private ownership and commerce goes back to Roman law. Legal historian Yan Thomas showed that Roman law used a distinct legal category, called ‘pecunia communis’, for goods designated as non-appropriable by private individuals.[17] This legal category applied to two types of goods: ‘res sacrae’ (‘sacred things’) and ‘res publicae’ (‘public things’). Among the sacred things, Thomas listed objects and places used in the religious practice. The public things included objects and places such as water pipes, theatres, markets, and roads. According to Thomas, there was no clear separation between ‘res sacrae’ and ‘res publicae’ in Roman law, and they were both considered ‘common goods’. These were distinguished from ‘res in commercio’ (‘commodities’) by their function, that is, the fact that they were reserved for a common use.[18]

As both an expression of and a catalyst for community life, ‘common goods’ were seen as things for which there could be no monetary equivalent.[19] In other words, they were priceless. Viewed from this perspective, their exclusion from private ownership and trade is easy to understand. If their function as an expression of and a catalyst for community life is lost, they cease to be ‘common goods’ and they become ‘commodities’. In that sense, it is impossible to appropriate ‘common goods’ because they are beyond the reach of ‘singuli homines’ (literally ‘isolated men’).

Going back to the discussion about the Bible and the Constitution, I suggest that this could be a helpful way to think about what can and cannot be owned privately. Understood as ‘common goods’ in the sense illustrated by Thomas in his study of Roman law, both the Bible and the Constitution are at the same time a community’s statement of shared beliefs, and something involved in the making of that community. One cannot privately appropriate these ‘common goods’ and, thus, terminate their communal use without degrading their communal meaning.[20]

Therefore, one cannot be said to own the Bible in its communal sense. Yet, as the case of the Green Collection shows, one can own rare biblical artefacts and objects. But how rigid is the line of demarcation between those aspects of the Bible that can be owned and those that cannot? I suggest that, in practice, the separation might not be as clear. As owners of rare biblical artefacts, the Greens gain control not only over the manner in which these objects are represented, but also over how the story of the Bible itself is told through them. This, I have argued, has been used by the Greens as means to legitimate their understanding of what the Bible is, and of the social or communal status it should be given in believers’ lives (‘absolute authority’). In re-telling the story of the Bible, controlling its representation, and legitimising this interpretation, the Bible’s ownership may cease to remain beyond private reach.

[1] PhD Candidate at the Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, University of Oxford.

[2] Highlights of the museum collection can be found here: https://museumofthebible.org/museum-of-the-bible-collection.

[3] Details about Hobby Lobby’s Donations and Ministry Projects can be found here: http://www.hobbylobby.com/about-us/donations-ministry.

[4] ‘Museum Collection | Museum of the Bible’ <https://museumofthebible.org/museum-collection> accessed 18 February 2017.

[5] Joel Baden and Candida Moss, ‘Can Hobby Lobby Buy the Bible?’ (The Atlantic, January/February 2016 Issue) <https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/01/can-hobby-lobby-buy-the-bible/419088/> accessed 13 February 2017.

[6] Steven Green quoted in: ‘More than a Hobby’ (The Economist, 2 July 2016) <http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21701487-steve-green-man-building-bible-museum-washington-explains-what-he-up> accessed 13 February 2017.

[7] Noah Charney, ‘Critics Call It Evangelical Propaganda. Can the Museum of the Bible Convert Them?’ (The Washington Post, 4 September 2015) <https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2015/09/04/f145def4-4b59-11e5-bfb9-9736d04fc8e4_story.html?utm_term=.302dae2588fa> accessed 14 February 2017.

[8] ‘Biblicism’, the belief according to which the Scripture is ‘the central authority’ over a believer’s life, is one of the essential characteristics of evangelical theology. Arguably, this understanding of the Bible resonates with that promoted through the Green family’s charitable actions. See ‘Evangelical Theology’, Ian A McFarland and others, The Cambridge Dictionary of Christian Theology (Cambridge University Press 2011) <http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/oxford/detail.action?docID=691811>.

[9] The museum’s mission according to the tax filing for 2011: The Museum of the Bible, ‘Form 990 Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax’, <http://207.153.189.83/EINS/273444987/273444987_2011_09591cf7.PDF> accessed 14 February 2017.

[10] Michelle Boorstein and Michelle Boorstein, ‘Hobby Lobby’s Steve Green Has Big Plans for His Bible Museum in Washington’ (The Washington Post, 11 September 2014) <https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/hobby-lobbys-steve-green-has-big-plans-for-his-bible-museum-in-washington/2014/09/11/52e20444-1410-11e4-8936-26932bcfd6ed_story.html?utm_term=.d9cf0f2dbaa1> accessed 22 February 2017.

[11] For scholarly research which analysis the transformations of the biblical text throughout history, see Eldon Jay Epp, ‘The Multivalence of the Term “Original Text” in New Testament Textual Criticism’ (1999) 92 Harvard Theological Review 245.

[12] Steven Green quoted in: Joel Baden and Candida Moss (n 5).

[13] Quoted in: Alan Rappeport, ‘Family Behind Hobby Lobby Has New Project: Bible Museum’ (The New York Times, 16 July 2014) <https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/17/us/politics/family-that-owns-hobby-lobby-plans-bible-museum-in-washington.html> accessed 15 February 2017.

[14] Under intellectual property rights.

[15] Maurice Godelier, The Enigma of the Gift (University of Chicago Press, 1999) 206.

[16] Crawford Brough Macpherson, Property, Mainstream and Critical Positions (University of Toronto Press, 1978) 5.

[17] This term was used under the Empire. ‘Pecunia populi’ was the corresponding term used under the Republic. Yan Thomas, ‘La Valeur Des Choses’, Annales. Histoire, sciences sociales (Éditions de l’EHESS 2002) 1435; 1441.

[18] ibid 1434–1435; 1461.

[19] ibid 1460.

[20] A similar idea is articulated by philosopher Michael Sandel with regards to the commercialisation of certain higher value goods. Michael J Sandel, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets (Penguin, 2013) 96.